Integration and divison: Towards a segmented Europe?

The conference on 26-27 April was part of the EuroDiv project which aims to provide more knowledge on the implications of the current European crisis and on possible ways out of the crisis.

- Professor Erik Oddvar Eriksen coordinates the project.

- Professor John Erik Fossum coordinates the sub-project 'Law and democracy'.

It is widely held that the post-war liberal order that heralded in an international regime bent on promoting human rights, peaceful co-existence and free trade is facing unprecedented challenges. One set of challenges emanates from within and pertains to the manner in which the rise of neo-liberal economic globalism has challenged democracy and human rights, while fostering technocracy and corporate law. Another set of challenges is external, evident in various forms of populist-driven ethno-nationalist resurgences. In this mix, the role of media is Janus-faced; it may augment the echoes of populism, but it might serve to hold populism accountable.

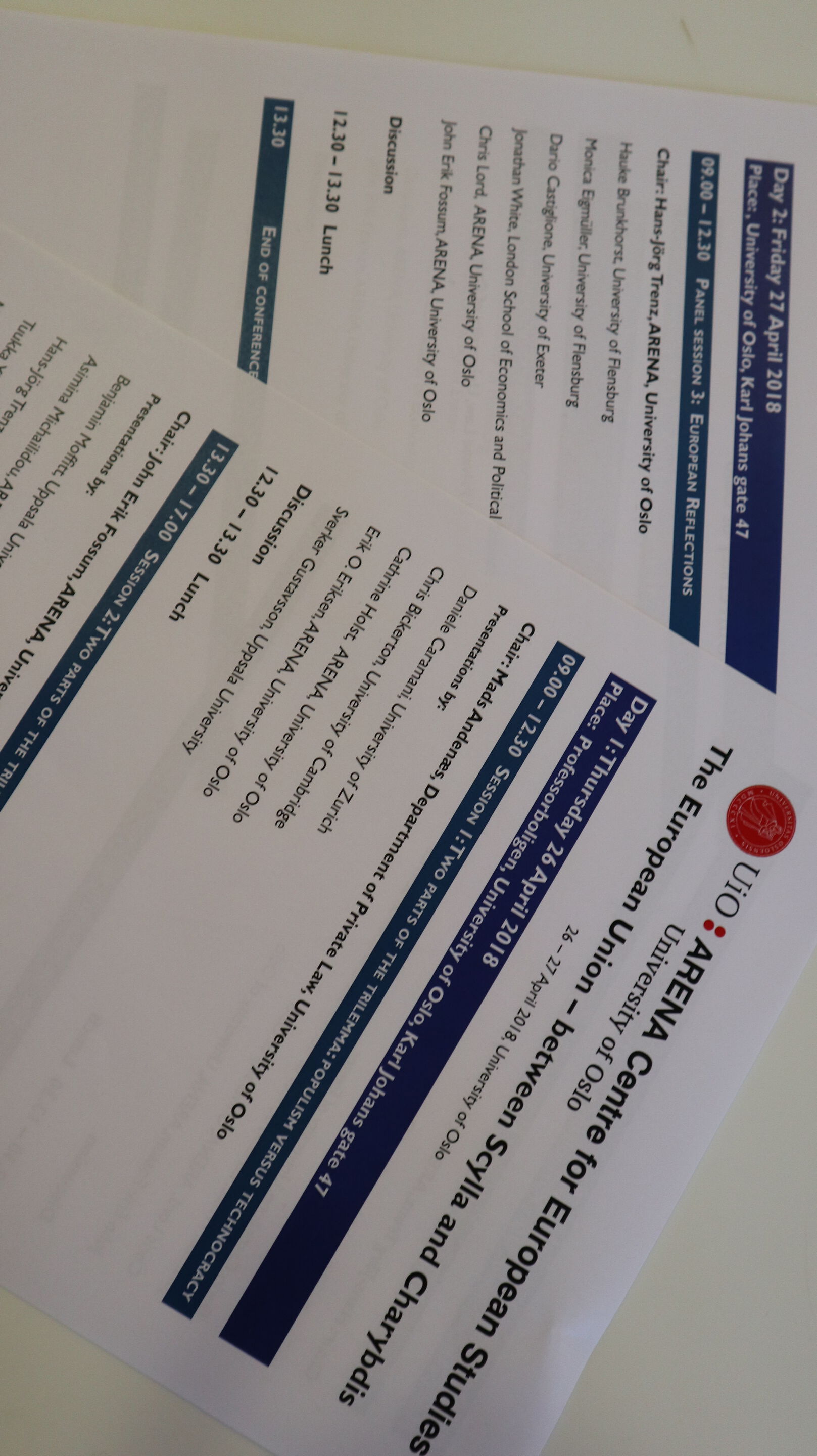

On the 26th and 27th of April, an international group of researchers met at the University of Oslo to discuss and reflect on these issues. The conference was co-organised by John Erik Fossum (ARENA, Oslo), Monica Eigmüller and Hauke Brunkhorst (University of Flensburg) as well as Mads Andenæs (Department of Private Law, Oslo) under the auspices of ARENA’s EuroDiv project. It was a follow-up of a major conference organised at the University of Flensburg in 2017 (many of the proceedings from that conference were published in a special issue of the European Law Journal).

The Oslo conference included political scientists, philosophers, lawyers, political theorists, public communication scientists, and sociologists from across Europe to discuss the interplay between

these challenges in the EU context, as well as

potential solutions.

Two parts of the trilemma: Populism versus technocracy

The conference’s first session, chaired by Mads Andenæs (Department of Private Law, University of Oslo) dealt with the relationship between populism and technocracy.

Daniele Caramani (Department of Political Science, University of Zurich) systematically compared populism and technocracy as alternative forms of political representation to party government, providing an overview of their main similarities and differences. A major difference is that technocracy highlights responsibility whereas populism highlights responsiveness. Furthermore, he argued that mediatisation exacerbates parties’ focus on short-term issues, leading to an over responsive party. He ended with discussing research results comparing public attitudes towards technocratic institutions and parties across countries.

Chris Bickerton (POLIS, University of Cambridge) presented ‘Macronism’ as a case indicating that populism and technocracy can also work together within the frame of party government. In order to move on to more stimulating conceptual debates the literature needs to better integrate the study of populism and technocracy. He proposed two routes: (i.) using representation and (ii.) addressing the relationship’s historical dimension.

Catherine Holst (ARENA and Department of Sociology & Human Geography, University of Oslo) discussed the role of academics in Nordic policy advice commissions. Having carefully examined a series of public and epistemic objections to experts’ involvement in policy-making, she tentatively provided a set of institutional mechanisms that can alleviate the problem of epistemic asymmetries.

Erik Oddvar Eriksen (ARENA, University of Oslo) discussed the challenges that non-majoritarian institutions pose to democracies, and their necessity within a complex policy-making environment. He argued that a sustainable legitimacy-repairing strategy lies in ‘epistemic publics’, where expert advice involves representative claims. By claiming knowledge constructs, epistemic actors act for something seen as important by the public.

Sverker Gustavsson (Department of Government, Uppsala University) took on a historical approach, pointing out that the current challenges faced by the EU cannot be solved by infusing classical post-Weimar remedies with new life. Instead, political parties must mobilize people across social, cultural and ethnic lines in support of democracy along simple ideas. Simultaneously, debates on the EU must move beyond the dichotomy of federalism vs. nationalism.

Two parts of the trilemma: Populism and mediatisation.

The second panel, chaired by John Erik Fossum (ARENA, University of Oslo), examined the link between populism and mediatisation.

Benjamin Moffitt (Department of Government, Uppsala University) provided an analytic framework for systematically assessing the relationship between media and populism. In addition, he addressed some central factors behind the limited literature on media and populism in the Western European context. Ultimately, while there is a correlation between media and populism, its direction remains unclear.

Asimina Michailidou (ARENA, University of Oslo) examined the relationship between crises, communication, and the role of social media. She carefully untangled the relationship between media and populism using the #Greferendum as a case study. Her analyses indicate that all parties used polarizing messages to increase visibility. Thus, while the eco-chamber effect is present in social media, it is an intended product rather than a random consequence.

Hans-Jörg Trenz (ARENA, University of Oslo/MCC, University of Copenhagen) in a paper co-authored with Charlotte Galpin debated the role of media in helping/discouraging rational deliberation. Assessing online discussion forums on mainstream news sites during the European Parliament’s election campaigns, the results presented suggest that social media is an uncivil sphere. Moreover, while commentators do not support the EU, or their national governments, they tend to support populist parties.

Tuukka Ylä-Anttila (University of Tampere) countered the assumption that populists valorise common sense over expertise, by analysing posts made on online forums in Finland. The results of his analyses point to a social communication of knowledge whether in the form of folk wisdom or alternative knowledge that denounces some experts. It professes belief in knowledge through inquiry, not from mainstream experts but from alternative ones. Closing, he called for research developing a more nuanced understanding of populism and the radical right.

Michael Hameleers (Amsterdam School of Communication Research, University of Amsterdam) provided a theoretical framework of populist communication that incorporated the dynamics between media and society. Considering the results from a body of his work, he argued that populist messages are selected by people who agree with the messages and the sources.

European Reflections

The third panel on the 2nd day, chaired by Hans-Jörg Trenz, aimed to link the previous day’s discussions and conclusions with the EU’s setting, and provide some directions forward.

Hauke Brunkhorst (Department of Sociology, Europa-Universität Flensburg) argued that populism has social and economic causes: political inequality is a result of social classes at lower levels mobilizing less than those classes at the top. According to Brunkhorst, to solve the issue of political inequality, the radical left is right; massive wealth redistribution and transnational deliberative democracy are necessary components.

Monika Eigmüller (Department of Sociology, Europa-Universität Flensburg) pointed out that to address populism in the EU we must understand the broad range of attitudes towards the EU within its member states, and central variables behind their variation. Presenting work assessing public attitudes towards the EU across countries, she argued that societal level has an impact on individuals’ EU support and scepticism across the board; underscoring the key role of education as a driver.

Dario Castiglione (Department of Politics, University of Exeter) argued that while populism and technocracy are exogenous threats to the EU, the real problem lies in Europe’s social dimension where the EU project lacks substance. To solve this issue, the project needs to add a social dimension through a re-structuring of representation; re-politicizing the EU project with a democratic dimension; disaggregating the term ‘populism’; forming an alternative to populism; and creating an inclusive European political vision.

Examining the rise of populism, Jonathan White (European Institute, London School of Economics) stated that over the last few years the EU has gone through a period of emergency where decisions are made out of necessity; overall disavowing agency. Populist parties appeal to the public due to their promise of giving agency back to the people, delivering ‘politics of volition’. This is also evident in the communication of volition as a form of non-conformity.

Examining the relationship between politics and technocracy, Chris Lord (ARENA, University of Oslo) juxtaposed Mills and Weber in the context of the European Parliament (EP). He argued that the EP acts as a working parliament, focused on producing quality legislative outputs through cooperation, but with limited interaction with public opinion. To solve this issue the EP requires some competition on the European level, and ongoing debates that are publically visible.

Closing the conference, John Erik Fossum (ARENA, University of Oslo) discussed the need to revisit theory of segments and segmentation in order to understand the EU’s structural mutations. He explained that the post-crises EU has emerged as a fledgling segmented political order based on two tracks: (i.) the community method that involves technocracy and horizontal divide, and (ii.) the intergovernmental system. These two tracks and their interaction create pathologies. By assessing the different segments, we can better understand and provide solutions to the problems faced by the EU.