More than half of the master's students at the Department of Social Anthropology (SAI) who were going abroad the previous year have been forced to interrupt their fieldwork as a result of the pandemic. With fewer travel restrictions, it is now becoming easier for aspiring anthropologists to go back to fieldwork again.

Sarah Mahoney has been involved in fieldwork in Japan during the pandemic. She is both a Japanese and American citizen. Sarah actually lives in California, and wrote her Bachelor's thesis at the University of California, Irvine (UCI).

“My Bachelor’s thesis was about old wooden homes in Kyoto that were being renovated and repurposed into cafes, guesthouses and community spaces. I was interested in the revitalization process,” she says.

When Sarah applied for a Master's degree, it was her supervisor at the UCI who told her about SAI. Sarah applied and was accepted. Over the past year, she has followed the courses at Master’s level via Zoom.

Once her field work is completed, Sarah plans to travel to Norway for the first time.

“I’m impressed by how flexible the lecturers have been when it comes to the difficulties with the different time zones. The digital classes have been fine as well, but it has been more difficult to connect with the other students," says Sarah.

“I think the foreign students who were not in Norway over the past year have felt a bit isolated from life on campus in Oslo and the others who are following the courses online. I’m sure this is difficult to avoid given the current situation," she says.

Anthropology in pandemic times

Japan has had strict infection control regulations and restrictions on entry. Nonetheless, the Master's student at SAI expected everyday life as a visiting anthropologist to be more difficult.

“I arrived in Japan in the spring and had to do quarantine in Tokyo. It was really scary. High infection rates, and everyone around me wearing double face masks. But then I moved out into the countryside, to a rural village where there are only 1,400 inhabitants. None of the villagers here have been infected," says Sarah.

“The village is quite self-sufficient therefore I did not feel the impact of covid as much as in the city,” she says.

Nevertheless, the anthropologist takes certain precautions: She keeps her distance and wears a face mask where necessary. More than half the population is over 65 years old. That's why Sarah's there, to talk to those who may not be around for so long. And to the young people who have started settling in the village.

Eight million homes stand empty around Japan, the country with the highest proportion of elderly residents in the world.

“I carried out a group interview yesterday at a community center for elderly. All the residents had been vaccinated, but we held the interview outdoors. Even if the chances are slim, I'm anxious about infecting someone," says Sarah.

Degrowth

Sarah Mahoney is to write her Master's thesis on depopulation in Japan, and possible future scenarios in areas where growth is no longer the guiding principle. She links her work to theories from the degrowth movement, in which key figures include anthropologist Jason Hickel and economist Giorgos Kallis.

“A number of young people from the city have started moving here. They are a source of new activities, such as a microbrewery and a hotel, she says.

"In Japan, rural areas play a key role in the concept of a sustainable future," says Sarah.

Sarah explains that the people she has met so far during her fieldwork have been friendly and open.

"Whenever I meet an interlocutor, I often get tips about someone else I can contact," she says.

The zero-waste town

Sarah Mahoney’s plan is to spend three months in the village, before returning to the United States to get vaccinated. She will then spend three months in another village, about the same size.

The rural town Sarah resides in at the moment is known in Japan as a zero-waste town. She explains that in the past, the residents burned their rubbish. This caused problems for the environment and raised concerns about increased carbon levels.

“In response, the town developed a zero-waste concept, based on a recycling program with 45 different sorting categories”, she says.

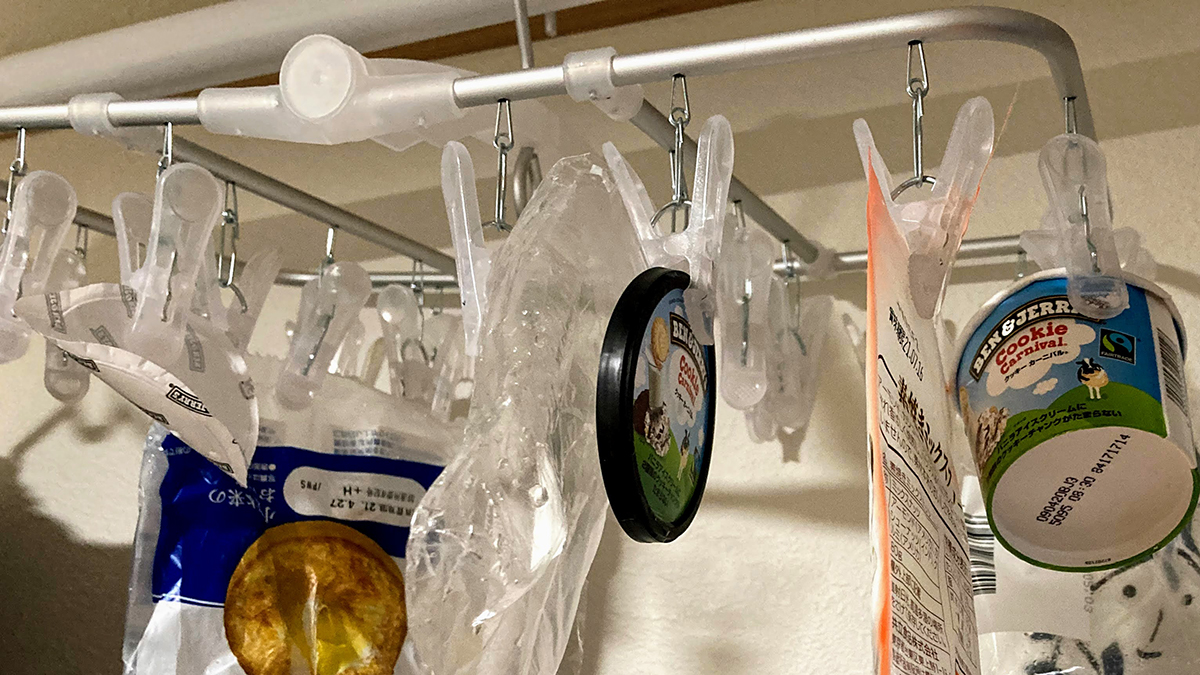

Ice cream cartons hung out to dry

When Sarah Mahoney first arrived there, the anthropology student at SAI found it difficult to have to separate, clean and dry the plastic packaging each time she made food.

“We use laundry hangers to dry our plastic trash. It is funny, because people who see my trash immediately know that I really love ice cream," says Sarah.

There are some elderly who are unable to sort their trash, so this is one big challenge for the town with a high elderly population, according to Sarah. However, there are also elderly who live self-sufficient lives deep in the mountains and do not use much plastics.

"So they have very little plastic waste," she says.

Despite the demographic challenges of the town, Sarah thinks the residents are trying their best to keep the town in existence while moving in a more sustainable direction.

“As part of my fieldwork, I have accompanied the workers who pick up waste from older people who are not able to get to the recycling stations themselves,” Sarah says.

Reassessing the future

The zero-waste concept is currently a crucial part of the town’s plan for revitalization, according to Sarah Mahoney. The newly established brewery markets itself as a zero-waste brewery. The hotel has a profile as a zero-waste hotel.

“Another example is the Kuru kuru-store. Kuru kuru means circulating in Japanese. People bring things they no longer use to the store. The objects are weighed on a scale and logged in a book. This allows the store to keep track of how much waste that does not end up at the dump. The residents can come to the store and take things they need back home with them,” says Sarah.

She explains that her roommate has furnished the entire house they share with objects from the Kuru kuru store.

"There are certainly some interesting things going on here. What is interesting is that rural Japan has become a place to experiment new ideas around sustainability and ways of living," Sarah continues.

"I also think the pandemic has caused a lot of people to rethink our future direction. In my opinion, degrowth is an exciting concept that merits investigating if we want to make our communities more sustainable," she says.