This blog post is based on the C-REX Webinar series Global perspectives on the Far Right. Click here to watch the recorded session with Naoto Higuchi, or to sign up for the webinar programme. The next session will be held on May 5th at 09:00 CEST, in which Jordan McSwiney will talk about the far right in Australia.

Although many regard Japan as a right-leaning society, it has not encountered xenophobic movements in the last century. Since the turn of the century, however, we saw the rise of nativist movements, which led to enactment of the Anti-hate Speech Law in the country. So, has Japan’s civil society moved to the right? To answer the question, I illustrate the three-layered structure of Japan’s far right—survivors of prewar fascist organizations (neo-fascists), the religious right and war veterans, and nativists—and examine how each layer has changed in this century.

Each of there three layers has something in common with its Western counterpart. While the first layer is reminiscent of Italian fascist organizations in terms of its ideologies and continuity from the prewar era, the second layer has a resemblance to the American Christian right in the sense that it has great influence on politics. The third layer seems much the same as European xenophobic movements in terms of hostility toward ethnic minorities.

The fall of fascist organizations in the Cold War era

The first layer of the Japanese far right is composed of neo-fascist organizations, which are characterized by strong faith in emperor-centered nationalism and anti-communism. Ordinary citizens are generally afraid of neo-fascist movements, which include quasi-outlaw cadres with connections to the mafia, making mass mobilization impossible. Instead, they assert their presence using items such as fatigue clothes and big sound cars. With martial music playing from loudspeakers on vehicles, they intimidate not only their enemies, but also the general public, with threats.

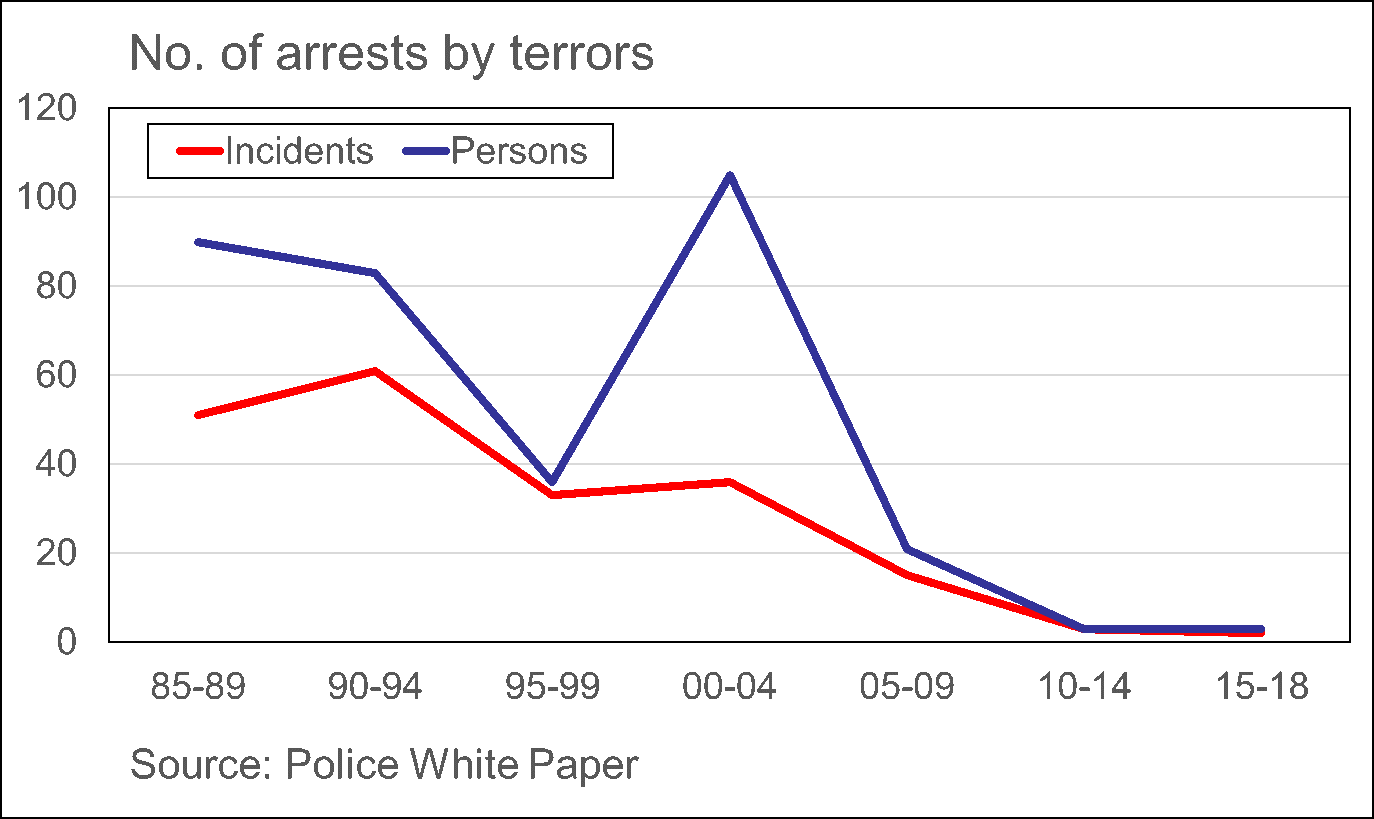

This first layer of far-right organizations has been on the decline since the collapse of the Soviet Union, as their insistence on anti-communism has made them outdated. Although they have engaged in terrorism targeting their enemies (e.g., North Korean organizations), the figure below shows the fall of terrorist acts committed by these fascist organizations. They have become powerless to the extent that the number of terrorists from this generation nearly dropped to zero in the 2010s.

Gradual decline of far-right lobbyists

The religious right and groups of war veterans (and their families) make up the second layer of the Japanese far right. They are characterized by strong political influence and insistence on historical revisionism as well as traditional ethics and emperor-centered nationalism. The common aim of the second-layer organizations is anachronistic: they glorify the prewar polity and imperialism that were dismantled after the war, and struggle to resurrect it. In 1997, two big associations merged into the Japan Conference to serve as the national center for the second layer of the far right, maintaining strong influence on some policy processes.

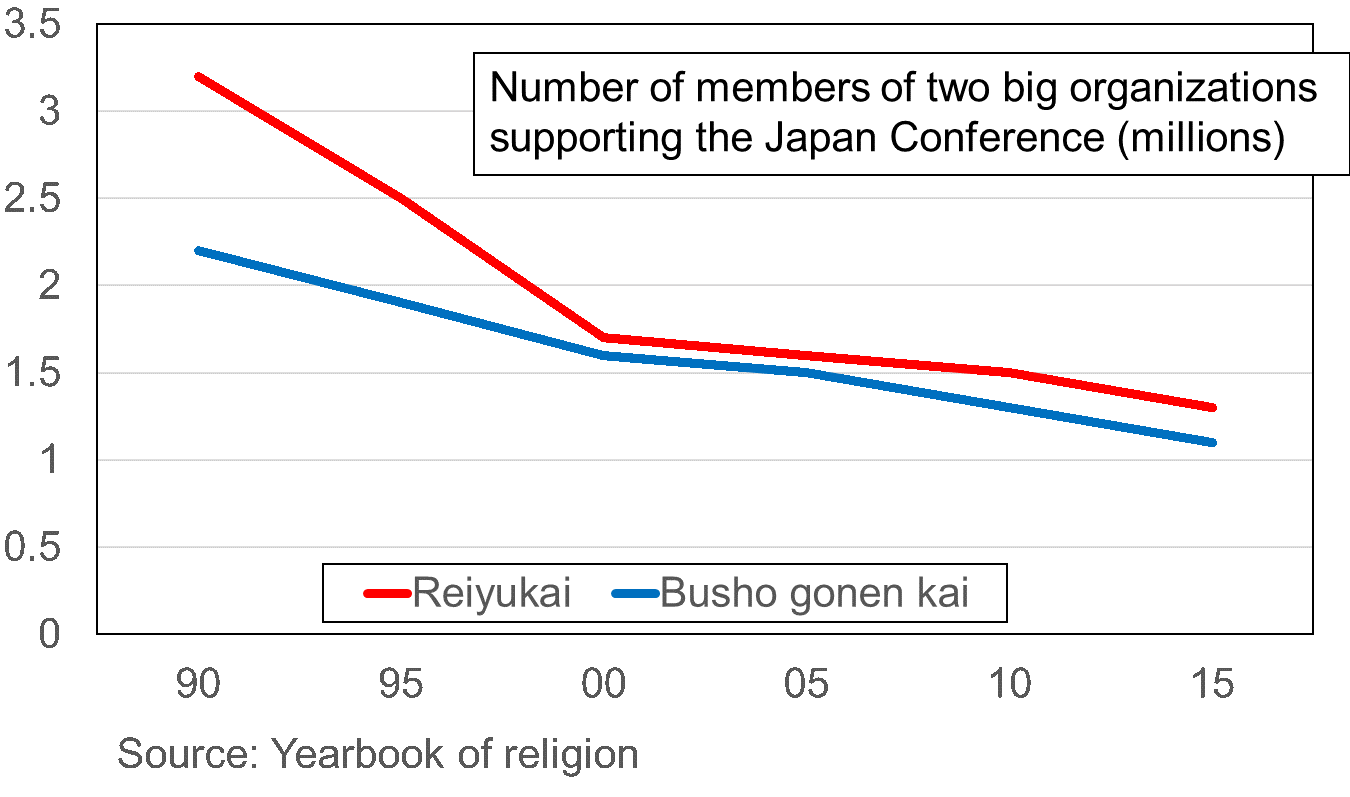

Their political power comes from a close relationship with conservative politicians: the Japan Conference has effectively lobbied through a group of MPs in the Parliament called the ‘Diet Member Council’, who are mostly from the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP). Their capacity for mass mobilization is based on large groups of religious and war veteran organizations across the country. Although support from these groups has enabled effective lobbying, far-right lobbyists have lost influence as time passes, because of the aging of their support base (this is especially the case of war veterans and their families). The figure below indicates religious organizations are also on the decline: in addition to the inevitable wave of secularization, a large-scale terror attack by the AUM Shinrikyo sect in 1995, in which its members released the liquid nerve agent Sarin into subways in Tokyo and injured more than 6,000 people, has pushed people away from religion.

The rise of nativism and anti-Korean hate

The third layer is exemplified by nativist groups such as Zaitokukai, which have been active since the late 2000s. It is the most recently established form of far-right organization, and the least dependent on existing social groups such as religious organizations and associations of war veterans. In other words, newly emerging far right groups have succeeded in mobilizing ordinary citizens unaffiliated with existing groups. A dominant feature of their activities is strong hatred towards Koreans, rather than other migrants. This is because Japan’s nativism is a variant of historical revisionism that legitimizes the Japanese invasion of Korea and China. Nativists are particularly triggered by the presence of Koreans in Japan, whose presence is a manifestation of stories that strike a discordant note in mainstream history: Koreans are a minority group who remind the Japanese of their past misdeed of imperialism.

Nativist movements are also characterized by the heavy use of the internet. It would be no exaggeration to say that Japan’s nativist movement, which started from a base that was close to zero, first materialized due to the affordances of the internet. For example, inexperienced ‘amateur’ activists gathered online to organize groups, which led to unchecked radicalization and in some cases led to criminal acts such as attacks on a Korean elementary school in Kyoto. Their relentless actions frightened Japan’s civil society and led some to organize nationwide anti-racist counter actions. The Japanese Upper and Lower House also passed the Anti-hate Speech Law in 2016 to contain nativist third-layer organizations.

Nevertheless, these new far right groups still survive in the midst of adversity. When Makoto Sakurai, the founder of Zaitokukai, stood for Tokyo gubernatorial election in 2016, he obtained 114,171 votes (1.8%). He received even more votes in the 2020 gubernatorial election, when he obtained 2.9 percent of the vote. These results show that the nativist movement is increasingly taking root in Japan’s civil society.

Mainstreaming of far-right organizations in the twenty-first century

As far as we have seen transformations of these three-layered groups of the far right in Japan, we can safely say their numbers are declining. Although we saw the rise of the nativist movement in the last decade, we have witnessed more rapid decline of neo-fascists and right-wing lobbyists. However, far-right organizations have become more influential within the political sphere, and have contributed to the mainstreaming of the far right in this century, as mainstream Japanese parties have shifted closer to the far right. Right-wing politicians like the former Prime Minister Shinzo Abe have become mainstream actors, and their reliance on far-right groups has resulted in the growing influence of the far right in Japanese politics.

.jpg)